A few weeks ago, I wrote about the proposal to make a new Capital Prep charter school in Middletown as part of a land development scheme. In order to better understand this case, it helps to understand its origin. Rather than an innovative or bootstraps success story, Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc was formed through the closure of a public school, not simply the “opening” of new school(s). Put simply, Capital Prep began as a small early college magnet school program and then grew at a school building that housed a bilingual program. Political actors closed this school and gave the building to Capital Prep to expand as an interdistrict magnet school that had a state-run lottery for numerical desegregation. Of particular note, this landmark school was taken from the mostly Puerto Rican and Latino children and families in that part of Hartford’s North End.

The case illustrates how local politicians and administrators implemented school reform towards choice and numerical desegregation in Hartford through a process of school closure and dispossession of access to the physical buildings and programming. And this process was later framed as choice. But it was interconnected with closures and state-funded creation or renovation of buildings to become magnets and charters that were sold as a commodity in a new market-based system. In this case, the situation was especially stark given that Barnard-Brown housed the city’s key bilingual program originally known as the Ann Street Bilingual School or La Escuelita.

Sitting just north of downtown Hartford, Barnard-Brown was built in the early 20th century. And despite being called a ‘castle-like” building almost a century later, the school had not been renovated since 1930. In addition to its location near downtown, its place and contents were very important for the city’s Puerto Rican community.

In the 1980s, Barnard-Brown and La Escuelita or the Ann Street bilingual school merged. This merger happened against opposition from PTO advocates at Barnard-Brown. Nevertheless once the schools merged, Barnard Brown was known for the bilingual education program that it had absorbed. Over the next two decades and by the early 2000s, the school had the highest proportion of students identified as bilingual (e.g., LEP, ELL, EL) in the entire district and among the highest in Connecticut. By merging with the former Ann Street bilingual program, the Barnard-Brown school building was one of the more visible remnants of Hartford’s Puerto Rican activism that had proposed bilingual education in the Civil Rights era.

Despite external challenges around accountability and economic disinvestment of the neighborhood, the school was endeared by families and students by many accounts. And the school was led for more than a decade by a former bilingual education teacher, Miriam Morales Taylor.

The Hartford Courant featured Morales Taylor’s rise from a Puerto Rican bilingual teacher with a formal education to being the principal of the Barnard-Brown school and resident of wealthy, suburban Simsbury, CT. The Courant story featured the contrast between Morales-Taylor’s rise to the suburbs versus the economic deprivation of the mostly Puerto Rican students and families attending and living near the school. The contrast was stark, but also reinforced negative depictions of the neighborhood and school. In other stories, the Courant also reinforced the labeling of Barnard-Brown as low-performing according to the NCLB Act of 2001. At this moment, this article and many other articles rarely if ever noted any lack of resources or funding to support this and other public schools.

A key turning point for Barnard Brown was 2005. That year Eddie Perez, the first Puerto Rican and ‘strong’ mayor of Hartford, named himself as chair of the school board. After being under a State-appointed trustee board, Perez became mayor, got a charter change to include a strong-mayor system, and got majority mayoral control of the school board after replacing the State takeover board. A former gang member and student at Barnard-Brown, Perez was arguably the most powerful political actor in Hartford at that time.

As chair of the school board and mayor of Hartford, Perez commissioned a facilities study for the Hartford Public Schools. And in 2006, the report surfaced, in part, at a school board meeting. The report included the possible replication of existing schools and closure of others, including Barnard Brown. The report also specifically mentioned dispersal of students at Barnard-Brown and replacement by either Capital Prep Magnet School or Pathways to Technology Magnet school. The plans in the report would have to wait, however, until a new superintendent came on board with the departure of Superintendent Robert Henry.

After bringing on a new superintendent in 2006-7, the Hartford School Board, chaired by Perez, moved forward with a version of the plans to close schools, reconstitute others, and replicate currently existing types of schools. The plan would create an ‘all-choice’ district by closing some schools, reconstituting others, and creating new types of schools including charter, magnet, and other theme-based academies. Like other places around the country, this reform was named a “portfolio” district similar to an investment portfolio that bought and sold private investments.

At the school board meeting, 500 teachers protested the plan as lacking collaboration with communities that would be most impact – parents, students, and teachers. Teachers wore pins reading, ‘respect,’ and the AFT leader Cathy Carpino delivered a petition with more than 1200 signatures protesting the lack of collaboration. As the Courant articles stated, “Police stood watch as classroom aides, teachers and parents delivered passionate speeches about their right to take part in the remaking of a school system that has employed many of them for decades.” In response, one appointed board member stated, ‘reassuringly’ before the Board vote. “We’re trying to provide choices for our kids so they can do well. We’re not trying to disrespect anybody.” Nevertheless, the Board forced choices on teachers and students that they did not want, need, or agree with at that time (Gottlieb Frank, 2007).

As mentioned, the sweeping plan to close, redesign, and create new schools eventually included the closure of Barnard Brown and replacement by Capital Prep. At the time, Capital Prep was a small, but growing magnet program. The program was located at the nearby Capital Community College, where the high school students could also take classes. According to one school board member, the permanent location of Capital Prep needed proximity to Capital Community College. This point on location was ‘critical.’ Barnard-Brown was roughly a quarter mile and within easy walking distance from Capital Community College. Both were adjacent to downtown Hartford and near the location of an area of the city previously slated to hold a stadium for the New England Patriots football team. The Patriots and stadium never came. But ideas on developing the area persisted, including the closure and replacement of Barnard-Brown.

Replacing a school like Barnard-Brown listed as ‘in need of improvement’ by the NCLB Act and the district redesign policy with a higher ‘achieving’ magnet school may have made sense at the time in dominant ways of thinking about school progress as test results. But the school was also far different than others. More than half the school was designated as LEP/ELL, the highest of any schools in the district. The school was a major point of entry for Puerto Rican families over the last several decades. And English speaking and reading often related to English-dominant test achievement.

As plans moved forward the summer before the Board vote, the district discussed their plan ‘redistribute’ and ‘relocate’ Barnard Brown students to nearby schools. The plan was to cause displacement of 450 students for the two hundred students currently at Capital Prep down the street.

The closure of Barnard-Brown displaced 450 students and the numbers at other schools help show the story. Nearby schools experienced large increases in enrollment, particularly of students identified as LEP/ELL displaced by the closure and planned replacement by Capital Prep. More than just a school, the closure and replacement by a magnet ended a chapter of a key Puerto Rican Civil Rights achievement – the creation of a dual-language, bilingual education program.

After a complete refurbish and renovation of the building, Capital Prep magnet school opened a few years later in the Barnard-Brown building. Featuring college-prep and, ironically, a social justice theme, the school became recognized for high graduation rates and the school’s brand. The library also featured a meeting space named after an original 1996 school desegregation case plaintiff, Elizabeth Horton Sheff.

In the years after the closure of Barnard-Brown, the Capital Prep magnet that took the building had virtually no ELL student and negligible rates of students with disabilities. And most of the school was Black or African-America with far fewer Puerto Rican and Latino students, which was the majority of the school before the building closure.

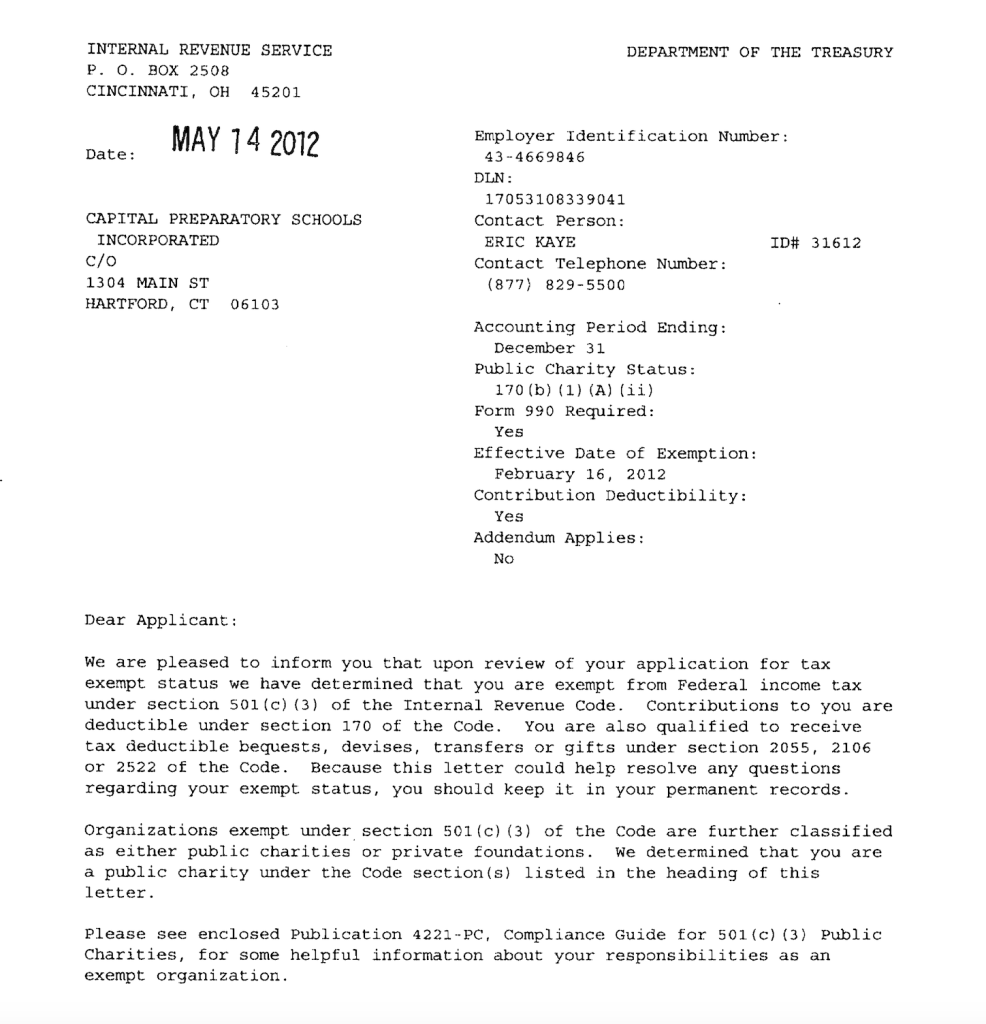

Years later, the school principal created a non-profit, charter management company 501(c) at the school’s address called Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc. With some assistance from the Superintendent at the time, this non-profit company became an enterprise meant to privatize public schools in Hartford. The original idea was for the principal and the administration to use the company to privatize the Capital Prep Magnet and ‘replicate’ Capital Prep in other public schools. This conversion of the public magnet school at an enclosed and dispossessed building into a private company to make Capital Prep a franchise was never approved by the Hartford Board of Education. Later, this same management company with the Capital Prep name would be used to launch new charter schools in Connecticut and New York while beholden – and paying fees – to Capital Preparatory School, Inc. As some theorists of political economy might say, the closing of a common school through dispossession of a building was a form of primitive accumulation of capital to start a private charter school company to make more money.

Perez’s successor after his resignation, Pedro Segarra, opposed the former principals’s plan to convert Capital Prep and another school under private management of this charter management company. However, a few years later, Segarra proposed creating a baseball stadium just south of Capital Prep, formerly Barnard Brown. The stadium for a private minor league baseball team was eventually built by public debt and Hartford still owes debt for that development.

In this case, dispossession of a school foreclosed on a Puerto Rican and Latino school with a legacy civil rights program in bilingual education. Furthermore, the dispossession of this public school enabled the profiting of the Capital Prep principal as the business under their name used the program and mailing address for a new company to create franchise schools with the same brand name. Importantly, this case happened in a liminal, gentrifying space between the central downtown district and the Puerto Rican and Black Clay-Arsenal neighborhood in the North End. To this date, the space is still contested.

Taking away a bilingual school and displacing mostly local Puerto Rican and Latino children to expand a selective magnet school for more advantaged Black and Latino children and families across the region was not choice for all. It was enclosure of a common school for the benefit of a few.

One thought on “Capitalizing on the Closure of a Latino School: The Case of Capital Prep Schools, Inc., – Part 2”