Several weeks ago, community advocates held a meeting online to share concerns about a proposal to start a semi-private charter school in Middletown. Most people in this group had major concerns about the negative impact of a new charter school managed by a private company. Many issues emerged such as the possible use of a youth prison, issues of how charter schools work compared to public schools, and how the former would impact funding for the latter. Later, I noted that the new charter school proposal resembled a land redevelopment scheme more than an improvement of educational opportunity (Part 1).

But there was one person in the discussion that worked for the charter school company that framed the debate as one about “choice.” In other words, their argument was that families should have more “choice” of schools. In this case, choice was nearly argued as the goal of education. As we move forward, there are many unanswered questions about the idea of making new charter schools and school choice more broadly.

As many scholars note, there are always potential issues of access and equity in school choice programs in terms of enrollment, curriculum, transportation, language, distance, and various supports. Adding to the complexity of the housing market connected to school enrollment, simply opening a new charter, magnet, or other school does not automatically or equally offer choice for all students and families. In short, school choice can exacerbate inequity in public education and its broader social context.

Still, many school choice programs, including charter schools, are often sold as a “choice.” But proposals for new charter schools such as Capital Prep are not entirely about choice. Instead, I would argue that this type of organizational set up with a semi-private charter school connected to a private management company is more about selective enrollment that also further siphons money away from public schools.

First, let’s look at Capital Prep’s record of selective enrollment or choosing their students. As I noted in my last post (Part 2), Capital Prep was founded as an early college program with a small number of students. Since the beginning, that school had selective enrollment by a. being a magnet school and b. displacing mostly Latina/o/x students that were at the Barnard-Brown school building. Once these children were displaced, Capital Prep magnet then enrolled new, other students through the state-run interdistrict magnet school lottery.

As State auditors noted a decade ago, Capital Prep Magnet did not even always follow the magnet school lottery and admitted students outside the lottery at least for some period of time. Capital Prep Magnet School was, to some degree, choosing its students while claiming to provide families a choice. And this selectivity undermined the numerical goals of school desegregation under the Sheff v. O’Neill agreement with the State of CT.

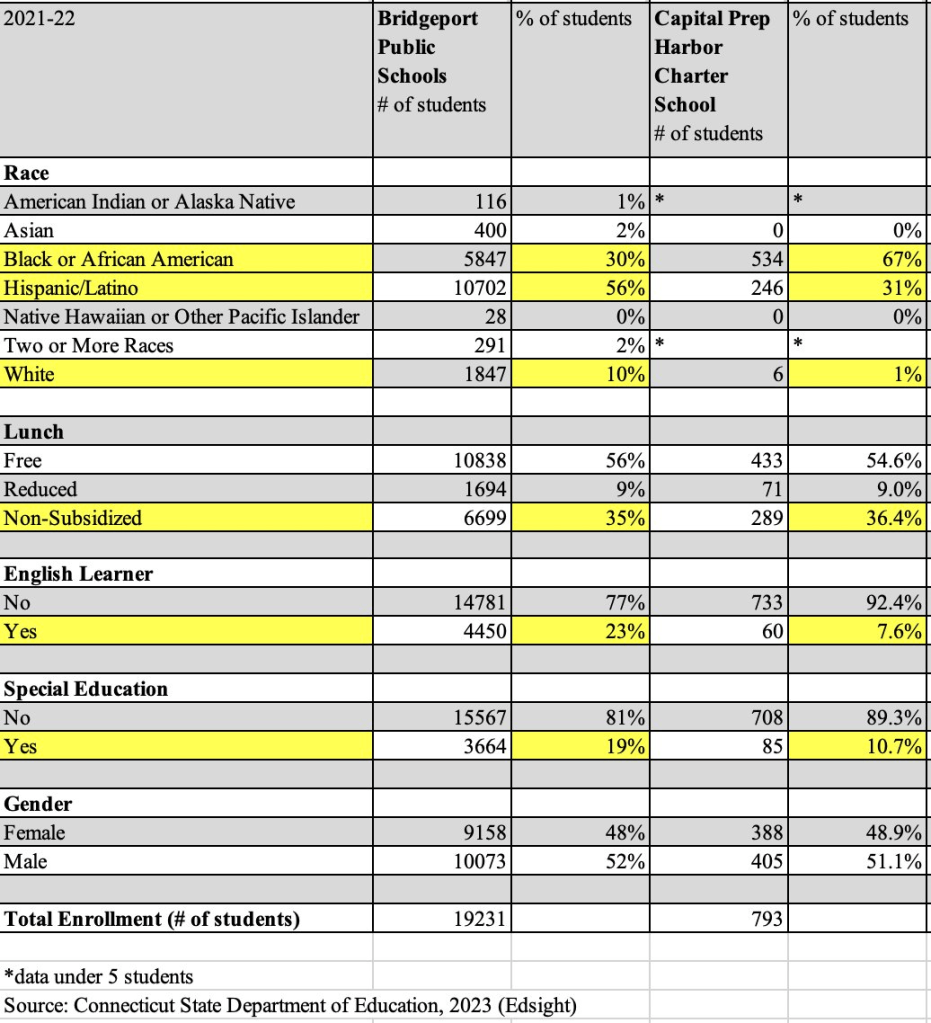

This pattern of major differences in student demographics is a broader issue. And selective enrollment may also be the case with the Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc. brand. Over the last decade, the private charter school franchise formed from the magnet school expanded in Connecticut and New York. As an example of differences in enrollment, take a look at Capital Prep Harbor School in Bridgeport, CT. In terms of enrollment, Capital Prep Harbor Charter School in Bridgeport had 7.6% of students identified as “English Learner” and 10% of students in special education for last year (2021-22). However, Bridgeport Public Schools had 23% “English Learner” students and 19% students in special education.

Enrollment data can show the stark reality of market-based education policy. But why is this major difference in enrollment happening? It can be policies, but also practices. For example, Capital Prep Harbor charter school has a sports or staff participation requirement to enroll at the school. What if a student can’t meet that requirement for some reason such as time, transportation, or some health or physical experience? That is merely one example of how to selectively enroll kids and families by not only creating, but advertising these requirements. In other words, students and families are offered a school option on paper, but the choices may not be available to all in practice.

Comparing Enrollment at Bridgeport Public Schools and Capital Prep Harbor Charter

In addition to these major enrollment differences, Capital Prep Harbor School is more racially isolated than the Bridgeport Public Schools overall. In other words, there is a higher proportion of BIPOC children in this charter district compared to Bridgeport Public Schools district overall. And the Black and Latina/o/x populations are reversed in these two districts: Capital Prep Harbor is 67% Black or African American and 31% Latino while the Bridgeport district is 30% Black or African American and 56% Latino.

To be sure, there are many possible reasons for these differences. Most importantly, the problem is not that there are more children of color in a particular school. Children, families, and even educators in these schools more often need more funding, smaller class sizes, support towards improvement, community engagement, culturally relevant pedagogy and curriculum, and more teachers of color. The lack of timely and appropriate school, district, and/or state response to these needs is part of why families may want alternatives. But rather than the State addressing racial inequalities in public schools, a semi-private school system such as charter schools may reproduce this inequality in new ways.

Percentage of Students of Color (BIPOC) by School District in Connecticut ’22-23

Like other charter schools in Connecticut, this case also raises questions about one of the original goals of charter schools to reduce racial isolation. The fourteen school districts in Connecticut with the highest proportions of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are charter schools. There are some schools (i.e., Common Ground charter school) that enroll student populations that are racially similar to the local districts by the numbers. As many scholars and my Choice Watch (on Connecticut) report noted a decade ago, the secondary school choice market can result in a revised version of the racial, class, and ability segregation of schools done in the past using school district lines.

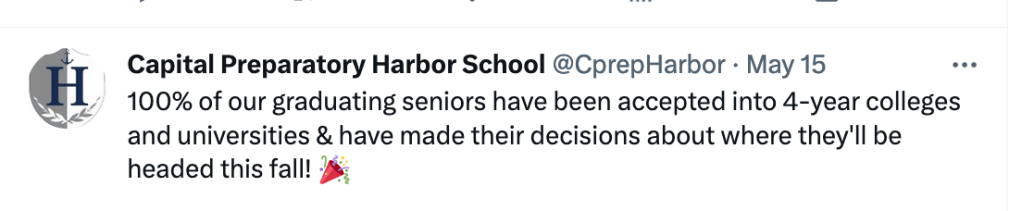

This selective enrollment can also have an impact on the supposed overall results of a school or district. Take graduation and college attendance data claims, for example. The Capital Prep Harbor School recently advertised that “100% of our graduating seniors have been accepted into 4 year colleges and universities.” That’s great news, right? Of course this is great news for those particular students.

But looking further into the numbers, it turns out that in 2021-22 there were 56 students in the 11th grade at Capital Prep Harbor Charter School. But this year (2022-23) there are only 43 students in the 12th grade. That’s almost a quarter of the class – 13 students – that did not go from grade 11 to 12? Where did these students go? Did they not fulfill some requirement to get to senior year? Were they pushed out of the school? Did they make another “choice”? In part, this cohort attrition is an issue with how graduation rates are now calculated. But it also shows the limits of simple numerical claims of success.

Many unanswered questions. Why did the appointed State Board of Education push a new charter school that even the State Department of Education raised questions about? Did the State Board of Ed. know about these enrollment differences and attrition in this and/or other cohorts? Why does the State Board of Ed. ignore state law on the policy goal of reduced racial isolation in charter schools?

Second, there are more questions about money. As many scholars note, charter schools can pull away resources from public schools. In Connecticut, public schools combine local and state public funds that are based on a need-based formula (in theory) and legislative approval. While drawing on public funds, public schools are accountable to local school boards, local administration (i.e., districts), finance boards, city councils, mayors, and the State.

Charter schools get roughly $11,000 in state public funds on a per student basis to fund the school. Run by private, self-selected boards, these schools report to the State Board of Education every few years and, for some, a Charter Management Organization (CMO) like Capital Prep Schools, Inc. Charter schools also pull away public school district funds through special education, transportation, and can redirect new state public funds that would have otherwise gone to public schools.

This may put charter schools at financial advantage and also create new financial problems. The students at Connecticut charter schools are most often more Black and fewer Latina/o/x, but also slightly more advantaged than the students still at public schools in terms of language, disability, income, and other categories. This selectivity and funding can be interconnected.

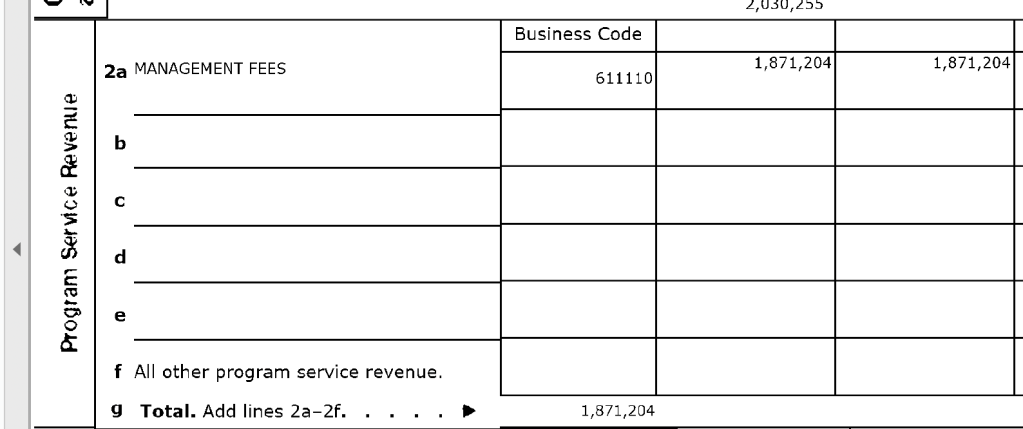

In addition, many charter schools also pay fees to private charter management companies (CMO). In Connecticut, the limit that charter schools can pay these fees is now ten percent (10%) of public funds redirected to the private CMO companies. Although it is very murky, we can follow some of the money.

In the 2020 (form) tax submission from the Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc. that private company brought in $1.8 million of fees taken out of charter school budgets. In other words, fees from various charter schools helped fund a whole other private organization outside of the charter schools.

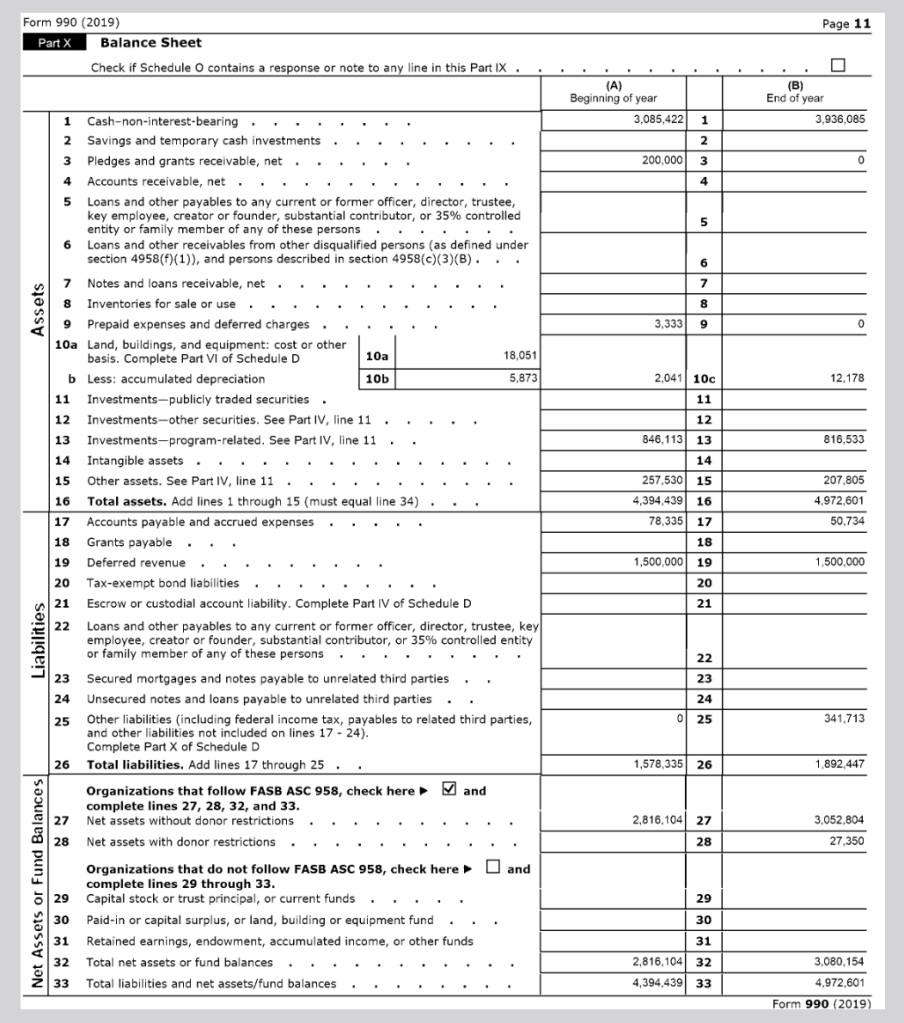

As we examine these fees, it is important to also remember that charter schools are technically their own districts and already have leadership teams. So the Capital Prep School, Inc. organization uses public money directed to charter schools to help fund a private company that is separate from the school(s) and district. In 2019, the Capital Prep Schools, Inc. private company also paid eight employees more than $100,000 in salary and benefits. Based on this document, it was unclear how these employees were working with any Capital Prep charter schools. Some might say this resembles a public district administration (i.e., “central office”). In other words, CMO’s may behave like a district central office. But does this arrangement contradict the way charter schools were sold as innovative and in need of independence from a district and public accountability?

The total amounts also raise questions about long-term issues. In the 2020 tax form, Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc began that year with $4.3 million and ended with $4.9 million in total liabilities and net assets/fund balances. Comparing spending and costs, Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc. ended the tax year with a positive balance of another half million dollars.

How much is Capital Prep. Schools Inc. accumulating from taking resources away from public schools? How does this taking of public funds to give to a private, unaccountable company help the goals of public education in this state? If charter schools are in need of more funds, as some would argue, shouldn’t these funds all be going to the charter schools rather than the Capital Prep Schools, Inc. company? These are unanswered questions.

These situations are currently allowed by law with some regulation mostly on reporting at the charter school level. In other words, you can FOIA request most public info from Capital Prep Harbor School, but not Capital Prep Schools, Inc. Only these 990 forms are available from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Several scholars have also raised questions about how the holes in this regulation of this system can allow for various forms of corruption, waste, not directly serving students, and undermining of public education more broadly.

Finally, many students can do well in some charter schools. The same is true for many students in public schools. And some charter schools do meet the broad goals asked by the State Board of Education. However, arrangements like Capital Prep with charter schools connected to private charter management organization (CMO) raises questions about selectivity, accountability, funding, and racial isolation.

Based on the background of the Capital Prep franchise, a proposed program may help a slightly more advantaged group of Black and Latina/o/x group of children while enriching a private company named Capital Preparatory Schools, Inc. But that proposal of shifting up to 700+ students along with the $11,000+ per student/per year in new state funding would also undermine the public schools in Middletown that would still have to serve children that live in that city. Middletown Public Schools will not only lose students and funds, it will likely be set up for its potential permanent public school closure(s) down the road. This process has happened in other cities around the state and country.

Shouldn’t the State provide more adequate funding and support in existing public schools, particularly those that serve children with more need? What about Bridgeport, Danbury, Hartford, New Britain, New Haven, Windham and other public school districts that already have Black, Latino, Asian, and Indigenous children and families that need more support and engagement now? There are better policy responses rather than selling more “choice.”